With Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One still dazzling viewers across the nation, I thought it might be fun to talk about one of my beloved childhood books, which is—as you may have guessed—about life inside a video game. Press enter for Gillian Rubinstein’s Space Demons!

Here’s the first paperback edition’s back copy:

They came pouring across the screen like alien and menacing insects. Excitement hit him like a fist in the pit of his stomach. Life suddenly seemed more interesting. He re-set his watch and began to play Space Demons again.

The description emphasizes the visceral reaction evoked by the game, and implies its habit-forming power, both of which the novel develops in memorable detail.

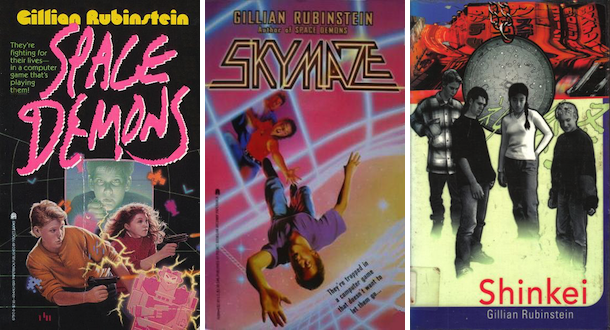

Space Demons was published in 1986, but it didn’t reach me until 1989, when I was ten years old. The cover of the 1989 Magnet paperback edition, the one I encountered almost three decades ago and, despite its beat-up condition, still cherish today, shows two boys floating in a sea of space and stars. Atop that same cosmic backdrop we find three deliberately pixelated and oddly menacing “space demons,” blasting what we soon learn are their distinctive “fiery orange tracers.” Despite the old adage about books and covers, I remember clearly how much this particular artwork made me want to read the book it graced.

Consider, too, this edition’s back copy:

Space Demons is a computer game with a difference. Imported directly from Japan, it’s a prototype destined to lock four unlikely individuals into deadly combat with the sinister forces of its intelligence.

And, as the game draws them into its powerful ambit, Andrew Hayford, Elaine Taylor, Ben Challis and Mario Ferrone are also forced to confront the darker sides of their own natures.

More than anything else, that last sentence intrigued me. Their darker sides? What could that possibly mean? To my ten-year-old self that sounded adult and sophisticated, not the kind of thing I was used to in adventure-oriented stories.

Now, I’ll grant you, as an adult one might reasonably suspect that the line about “the darker sides of their own natures” was editorial hyperbole, a hook to entice young readers with the promise of grown-up wares. Well, when you open up the 1989 paperback, right before Chapter One you’re greeted with this epigraph: “We has found the enemy and they is us.”

Pretty heavy stuff, I’ll say. (Curiously, as I discovered years later, the earlier hardcover edition published by Dial Books for Young Readers omits this variation on the quote by Oliver Hazard Perry.) If I hadn’t already succumbed to the peculiar charms of the book’s artwork and its tantalizing back copy, this ominous and poetically a-grammatical epigraph would have unquestionably done the trick. I was fully primed.

How quickly and deeply I became enraptured by the story, which begins like this:

“Go on, Andrew, have a go!” Ben was tired of playing by himself. He knew the sequence of the game too well. It was no longer a challenge playing against the computer. But if two people played against each other, the game was more unpredictable and more fun.

In real life I had yet to play a video game against another live player, and the idea instantly captivated me. (I’d get more than my share of this type of play in the following year, but it never lived up to its fictional depiction in Space Demons.)

Rubinstein constructs her characters deftly. Andrew Hayford is a confident twelve-year-old used to deploying his natural charm and charisma to get pretty much whatever he wants in life. He’s competent at everything, is from a well-off family, and as a result life is relatively effortless for him—leading to a kind of tedium. That changes with the arrival of the titular prototype game. By the end of the first chapter, Andrew experiences “a brief, chilling impression of the intelligence behind the game.” Naturally, this proves irresistible.

Over the course of the next few chapters we meet Elaine Taylor, whose mom disappeared two years ago, John Ferrone, the younger brother of one punkish Mario Ferrone, and a girl named Linda Schulz, who likes to claim that Andrew is her boyfriend. We follow these characters through their daily lives, learning about their friends, their family relationships, their goings-on at school, and their emotional landscapes. Rubinstein is incredibly deft at portraying their inner lives and doesn’t shy away from difficult situations, but she also leavens the proceedings with pitch-perfect humor. In fact, her control of voice and tone are outstanding. Consider, for instance, this throwaway moment in Chapter Three, which sees Andrew struggling in “maths” class:

Andrew had been working studiously at his maths problems, but after completing four of them at top speed he suddenly felt totally unable to do any more. “I must protect my skull,” he thought to himself. “Any more maths and it will be crushed beyond repair.”

I should mention that given the book’s original publication date, its technological elements are perforce incredibly dated, and some details may be incomprehensible to young readers today: computer cartridges, references to games by Atari and Hanimex, and so on. Ditto for cultural references, like Andrew’s blasé attitude towards a magazine he enjoyed when younger called Mad, and so on. But rather than distracting from the story, this lends the book a certain quirky charm. Why indulge contemporary curated nostalgia for the 1980s, like that in Ready Player One, when you can experience an authentic ‘80s tale? I’ll note, too, than when I first read the book, I was completely oblivious to Space Demons’ Australian setting, which is made pretty clear to anyone paying even a little attention. In my defense, I was probably turning the pages too fast.

Remarkably, Space Demons is Rubinstein’s first novel. I say remarkably because the novel feels like the work of a confident and experienced storyteller. Rubinstein manages to explore a plethora of difficult subjects affecting teens and pre-teens—broken homes, anxiety and self-confidence issues, bullying, social hierarchies, game addiction—with a light touch that never makes the reader feel overly aware of what she’s doing. The situations arise organically from the story, and the protagonists’ responses feel believable every step of the way. Andrew soon realizes that the new Space Demons “hypergame” consuming so much of his time and energy “responds to hate”—in precisely what way I won’t reveal. This serves as a natural gateway to expose the leads’ dislikes and insecurities. By Chapter Twelve, for instance, it’s impossible to miss that the discrimination experienced by Mario contributes to his self-hatred. (Marjorie, Andrew’s mom, is clearly racist, referring to Mario as “a foreigner” and commenting on how “he’s very dark”.) And yet in the context of the story, these insights feel neither moralizing nor gimmicky. Also, younger readers—as I surely did at the time—can lose themselves in the enjoyment of the narrative on a surface level, appreciating its clever turns, while older readers may appreciate the deeper metaphorical layers.

Finally, the novel does exceptionally well something that I think all of the best science fiction does. It directly couples the characters’ internal realizations and transformative insights with the main resolution of its what-if plot, so that one wholly depends on the other and they both occur simultaneously. Bravo!

Space Demons was quite successful, and three years after its publication was adapted for the stage by Richard Tulloch. Given its commercial and critical success, a sequel was perhaps inevitable, and in 1989 Rubinstein delivered a fine follow-up titled Skymaze.

Skymaze begins a year after Space Demons. Domestic situations, a key part of the first book, have evolved, with new friendships and conflicts underway. In response to a challenge by Ben, Andrew has sent off to the same enigmatic Japanese game designer of the first “hypergame” for the follow-up, and we’re off and running. Like its predecessor, this novel contains a sensitive and at times poignant portrayal of its young leads. In Chapter Three, for example, there’s a lovely passage where Andrew reflects on “some strong and unfamiliar emotions,” which include a kind of envy at the budding relationship between two of the other main characters and a touching realization that “once the three of them had faced one another with their defenses down.” The idea of bridging the gap across cultures and values, the importance of vulnerability and of not behaving rashly, recur throughout the trilogy.

Fear not: these psychological musings never bog down the story. Rubinstein is as adept at action and descriptive narrative, with plenty of rich sensory passages about what it feels like to be inside Space Demons or Skymaze, as she is at character development. In this middle book of what would become a trilogy, she does a great job of staying true to the characters, raising the stakes without going over the top, and expanding on the original idea with a new twist. It may not be as thrilling or surprising as the first volume, since we know the general gist, but it’s a worthwhile successor.

Which brings us to Shinkei, which appeared in 1996. Between the publication of Skymaze and Shinkei Rubinstein published a number of other books, and I suspect she took her time with the trilogy’s conclusion in order to make it as special as possible—something I can certainly appreciate. In her acknowledgments she thanks “the many readers who wrote and told me their ideas for a sequel.”

The new novel opens in Osaka and introduces us to Professor Ito, the mysterious designer of the first two novels’ plot-propelling games, and his fifteen-year-old daughter Midori. We learn that Ito’s wife died a while back, and that those first two games helped Midori deal with the loss of her mother (notice the absent-mom parallel with Elaine in Space Demons). Ito has been hard a work on a third game, but it’s grown beyond his ability to control. He wishes to destroy it, but the game won’t let itself be erased, and now various nefarious organizations are after him for it.

Shinkei’s opening chapters also present us with a second-person voice, a force of some kind, that appears to be influencing events at a distance, eventually helping to orchestrate the travel of Andrew, Elaine, and Ben to Tokyo, where they will meet up with Midori. This entity also makes contact with Ito’s assistant Toshi, Midori’s original co-player in the first two games. “We modified and changed the program,” Midori says. In her case, it was through “inner silence” rather than hate. “And now the program is trying to play us,” she concludes. “Shinkei,” it turns out, may be translated as “nervous system,” but originally meant “the channel of the gods” or “ the divine pathway.”

From a plot perspective, this book is more sophisticated than the first two, featuring more characters and intersecting storylines. Thematically, too, it enhances what has come before rather than merely retreading old ground. Shinkei’s observations about the power of technology to facilitate a connection between human beings, but also to lure us into isolation and escapism, and its lively speculations about an artificial intelligence crossing over from the mechanical to the biological, strike me as prescient. The story contains nice throwback references to the first two volumes, but more importantly provides a fitting resolution to the main character arcs. It also successfully answers the questions raised in Space Demons and Skymaze about the games’ origins.

I also want to commend Rubinstein for Shinkei’s Japanese setting; it becomes clear as you read that Rubinstein is fascinated by Japanese culture and writes about it with genuine respect and a deep-seated appreciation borne not only from serious study but actual immersion in the country. She compellingly evokes customs, geography, nuances of expression and lifestyle. How many science fiction novels aimed at young adult readers, for instance, contain, as Shinkei does, a Japanese glossary? Rubinstein, I later found out, has been drawn to Japan since she was a girl, and has visited the country and delved into its history with dedication throughout the decades. Case in point, under the name Lian Hearn, Rubinstein has since 2002 released two multi-volume series that imaginatively blend Japanese history and mythology: the five-book Tales of the Otori, set around the end of the 15th century, and more recently the Shikanoko series, set about three hundred years before that.

Revisiting childhood favorites is an enterprise fraught with peril, but in the case of Space Demons, it’s been an unalloyed delight. I’m forever thankful to Rubinstein, still prolifically active as a writer in her mid-70s, for penning these stories (and so many others) throughout her long and fascinating career. Her first novel held me steadily in its grip almost thirty years ago, did so again recently, and I expect will do so once more decades hence. What a remarkable introduction to the possibilities of science fiction. Not only did Space Demons live up to the promise of its enigmatic epigraph, dramatically illustrating how we has indeed found the enemy and the enemy is us, but it also convinced me that books themselves are the ultimate “hypergame,” providing fully enveloping fictional environments in which everything—even personal time travel—becomes possible.

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro is the author of the Hugo- and Locus-finalist Traveler of Worlds: Conversations With Robert Silverberg (2016). Alvaro has published many stories, essays, reviews, and interviews, as well as Rhysling-nominated poetry.

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro is the author of the Hugo- and Locus-finalist Traveler of Worlds: Conversations With Robert Silverberg (2016). Alvaro has published many stories, essays, reviews, and interviews, as well as Rhysling-nominated poetry.